What is melanin?

Melanin is a biological polymer that occurs in the skin, hair, and feathers of vertebrates, as well as in the back of the eyeball and certain regions of the brain and some glands. Melanins occur in insect cuticle and in the eyes and eyespots of most animals. Melanins also produce the black coloration in the ink of the squid and other cephalopods, and they act as protective agents in certain microscopic organisms. In humans, melanin is best known as the colouring agent that makes our skin black, brown, reddish, or yellowish.

The name ‘melanin’ comes from the ancient Greek melanos, meaning ‘dark’, and the term was probably first applied by the Swedish chemist Berzelius in 1840. Melanin has many biological functions, including colouring the skin and hairs or feathers, strengthening plant cell walls and insect cuticle, absorbing light (and so providing photoreceptor shielding, thermoregulation, photoprotection), and it is an important free radical sink.

There are three types of melanin, the first two of which have been identified in fossils:

- Eumelanin is the best-known form of melanin, providing primarily black colours. Eumelanin is found in the hair and skin of humans, and it colours the hair grey, black, yellow, and brown. Eumelanin exists in two forms, black eumelanin and brown eumelanin. Black melanin produces black colours when it is present in large quantities, and grey colours when it is rarer. Brown eumelanin may produce brown hair colours when it is present in abundance, but smaller amounts produce lighter brown, or blond, hair colours. The black variant of eumelanin is commonest in people of non-European descent, whereas ethnic Europeans more often have the brown eumelanin variety.

- Phaeomelanin (= pheomelanin) produces reddish colours. In humans, phaeomelanin is more abundant in the skin of women than men, and so their skin is slightly redder. It occurs also in hair, and provides the main colouring agent in ginger hair.

- Neuromelanin is the dark pigment that produces a black colour in certain parts of the brain.

The ink in the cuttlefish contains another type of melanin called sepiomelanin, the melanins in plants are called allomelanins, and the melanins in bacteria pyomelanins. Some melanins in Fungi, usually termed ‘fungal melanins’, are the simplest of all.

Many species of fishes, reptiles, amphibians, and crustaceans can change colour relatively rapidly, whether to camouflage themselves against changing backgrounds, or to flash a warning. In these species, the melanosomes are under hormonal or neural control, and they may be transported into certain skin regions.

Chemistry of melanins

The melanins are derivatives of the amino acid tyrosine. The enzyme tyrosinase acts to change the tyrosine into DOPA (3,4-dihydroxyphenylalanine), and then into dopaquinone. The dopaquinone can be converted to leucodopachrome and then follows one of two pathways to produce eumelanins (Figure B below). Alternatively, the dopaquinone can combine with the amino acid cysteine by two pathways to produce benzothiazines and phaeomelanins Figure A below).

Molecular structure of phaeomelanin (A) and eumelanin (B). [Diagram from http://photoprotection.clinuvel.com/node/204.]

Melanins and human health

Melanins have photochemical properties which make them act to protect tissues and organs from harmful ultraviolet (UV) radiation. Nearly all the UV energy is transformed into harmless amounts of heat. By this process, the melanin can reduces the generation of free radicals to a minimum,and so prevents indirect DNA damage which can produce malignant skin melanomas.

When pale-skinned peoples sunbathe, their skin goes first red, and then brown, as extra melanin is generated in the skin. The brown colour is a natural response to excessive sunlight, acting to protect the skin. But, the rays of the sun, may also cause gene mutations within the skin cells, and these can lead to excessive melanin production and the formation of black or brown skin tumours called melanomas. Melanomas may also arise from other causes, and they are especially prevalent in pale-skinned and light-haired people, and there may be heritable factors.

Absence of melanin in the skin results in albino forms, in humans and in animals. Reduced levels of neuromelanin in the brain is a result of Parkinson’s disease. Freckles, moles, and birth marks are also produced by concentrations of one or other melanin pigment.

Melanins have many additional properties, apart from protection of eyes and skin from harmful UV radiation. Further, their role in colouring human skin and hair gives them a key role in cosmetics. Combining these, it is perhaps no surprise that there is a substantial pseudo-scientific literature on the significance of melanins in medicine and beauty, and this spills over into somewhat speculative ideas about aspects of human evolution.

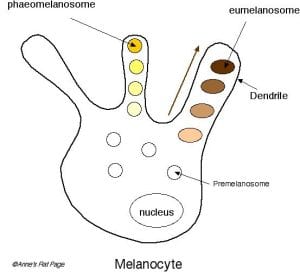

Melanocytes and melanosomes

Eumelanosomes are typically elongate (0.8-1 µm [800-1000 nm] long, and 200-400 nm wide) with rounded ends, whereas phaeomelanosomes are ovoid to sub-spherical and they vary more in size; most are between 500 and 700 nm long (occasionally up to 900 nm) and 300 and 600 nm wide. [Note, 1 nm, or nanometre, is one-millionth of a millimetre (one billionth of a metre); so 1 mm = 1,000,000 nm.]

Further reading

- D’Alba, L. & Shawkey, M.D. 2018. Melanosomes: biogenesis, properties, and evolution of an ancient organelle. Physiological Reviews 99, 1–19.

- Durrer, H. 1986. The skin of birds: Colouration. In Biology of the Integument 2, Vertebrates (eds Bereiter-Hahn, J., Matolsky, A.G. & Richards, K.S.), pp. 239-247. Springer, New York.

- Marks, M.S. & Seabra, M.C. 2001. The melanosome: membrane dynamics in black and white. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology 2, 738-748.

- McNamara, M.E., Kaye, J.S., Benton, M.J., Orr, P.J., Rossi, V., Ito, S. & Wakamatsu, K. 2018. Non-integumentary melanosomes can bias reconstructions of the colours of fossil vertebrates. Nature Communications 9, art. 2878.

- Nosanchuk, J.D., Stark, R.E. & Casadevall, A. 2015. Fungal melanin: what do we know about structure? Frontiers in Microbiology 6, 1463.

- Prum, R.O. 2006. Anatomy, physics, and evolution of avian structural colors. In Bird Coloration Vol. 1 (eds Hill, G. E. & McGraw, K. J.), pp. 295-353. Harvard Univ. Press, Cambridge.

- Raposa, G. & Marks, M.S. 2007. Melanosomes – dark organelles enlighten endosomal membrane transport. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology 8, 786-797.

- Riley, P.A. 1997. Melanin. The International Journal of Biochemistry & Cell Biology 29, 1235-1239

- Wasmeier, C., Hume, A. N., Bolasco, G., & Seabra, M. C. 2008. Melanosomes at a glance. Journal of Cell Science 121, 3995-3999.